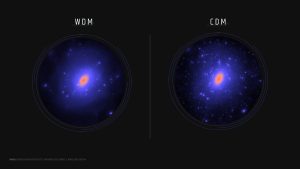

This image shows the result of two numerical simulations predicting the distribution of dark matter around a galaxy similar to our Milky Way. The left panel assumes that dark matter particles were moving fast in the early universe (warm dark matter), while the right panel assumes that dark matter particles were moving slowly (cold dark matter). The warm dark matter model predicts many fewer small clumps of dark matter surrounding our galaxy and thus many fewer satellite galaxies that inhabit these small clumps of dark matter. By measuring the number of satellite galaxies, scientists can distinguish between these models of dark matter. Image: Bullock and Boylan-Kolchin (2017); simulations by V. Robles, T. Kelley and B. Bozek, in collaboration with Bullock and Boylan-Kolchin.

In particular, the new results constrain the minimum mass of the dark matter particles, as well as the strength of interactions between dark matter and normal matter.

According to these new results, a dark matter particle must be heavier than a zeptoelectronvolt, which is 10-21 electronvolts. That’s one trillionth of a trillionth of the mass of an electron. This study also shows that dark matter’s interactions with normal matter must be roughly 1,000 times weaker than the weak nuclear force. Of the known forces, only gravity is weaker.

Read more here.